CITIZENS OF NOWHERE

THESIS PART I

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF BEIRUT, BArch 2013

While the topic of refugees is more relevant than ever, this thesis ended in 2013 and hasn’t been updated since.

Instead of two national states separated by uncertain and threatening boundaries, one could imagine two political communities dwelling in the same region and in exodus one into the other, divided from each other by a series of reciprocal extraterritorialities, in which the guiding concept would no longer be the ius of the citizen, but rather the refugium of the individual.

— Giorgio Agamben on Hannah Arendt’s We Refugees

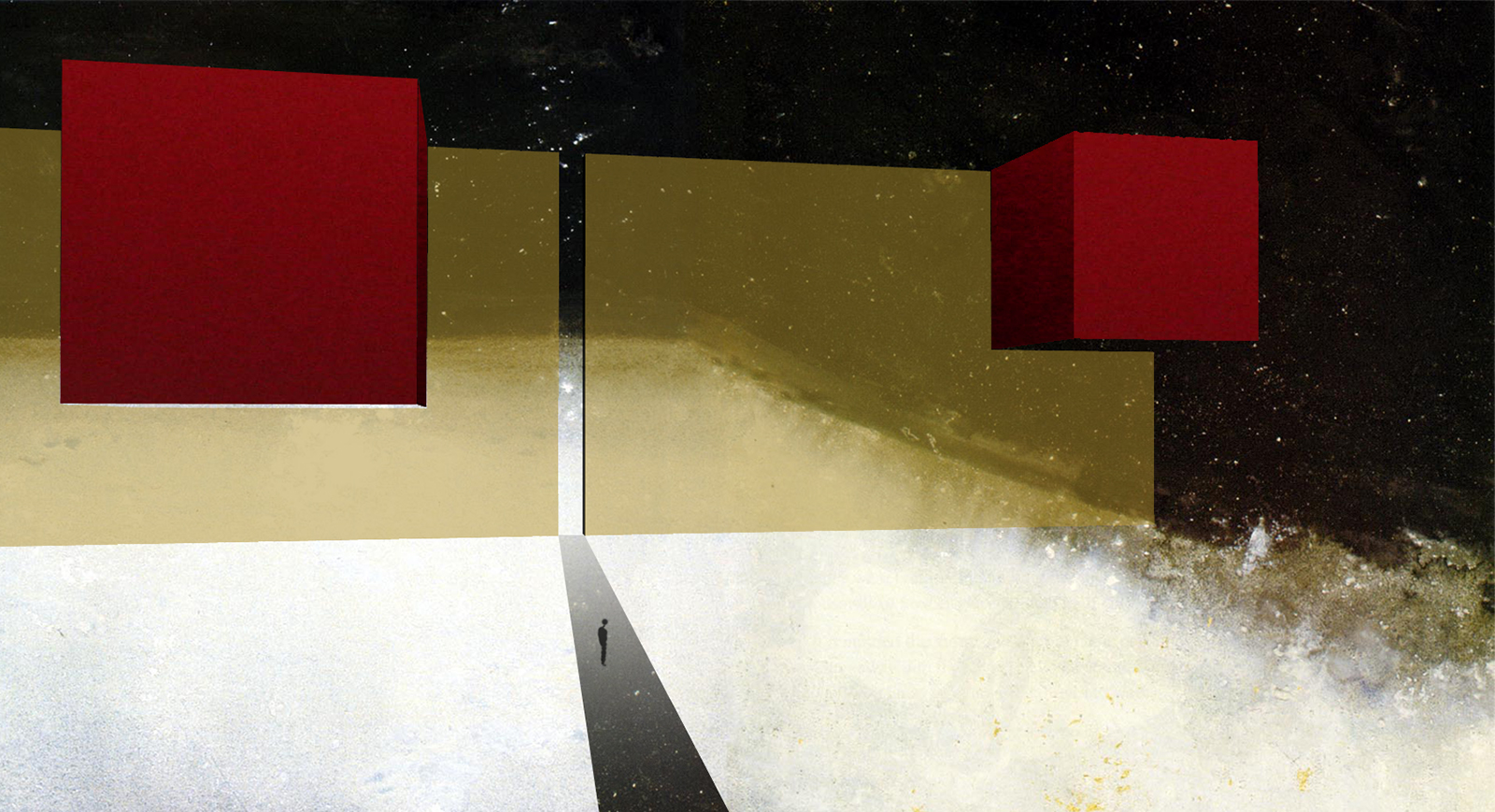

How can the concept of territory, or land, accommodate different forms of relations between people and the land, taking into consideration the status of the displaced (refugee) and the stateless (‘citizen’ of an extraterritory)? What are the spatial implications of such a person-land relationship?

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF BEIRUT, BArch 2013

While the topic of refugees is more relevant than ever, this thesis ended in 2013 and hasn’t been updated since.

Instead of two national states separated by uncertain and threatening boundaries, one could imagine two political communities dwelling in the same region and in exodus one into the other, divided from each other by a series of reciprocal extraterritorialities, in which the guiding concept would no longer be the ius of the citizen, but rather the refugium of the individual.

— Giorgio Agamben on Hannah Arendt’s We Refugees

How can the concept of territory, or land, accommodate different forms of relations between people and the land, taking into consideration the status of the displaced (refugee) and the stateless (‘citizen’ of an extraterritory)? What are the spatial implications of such a person-land relationship?

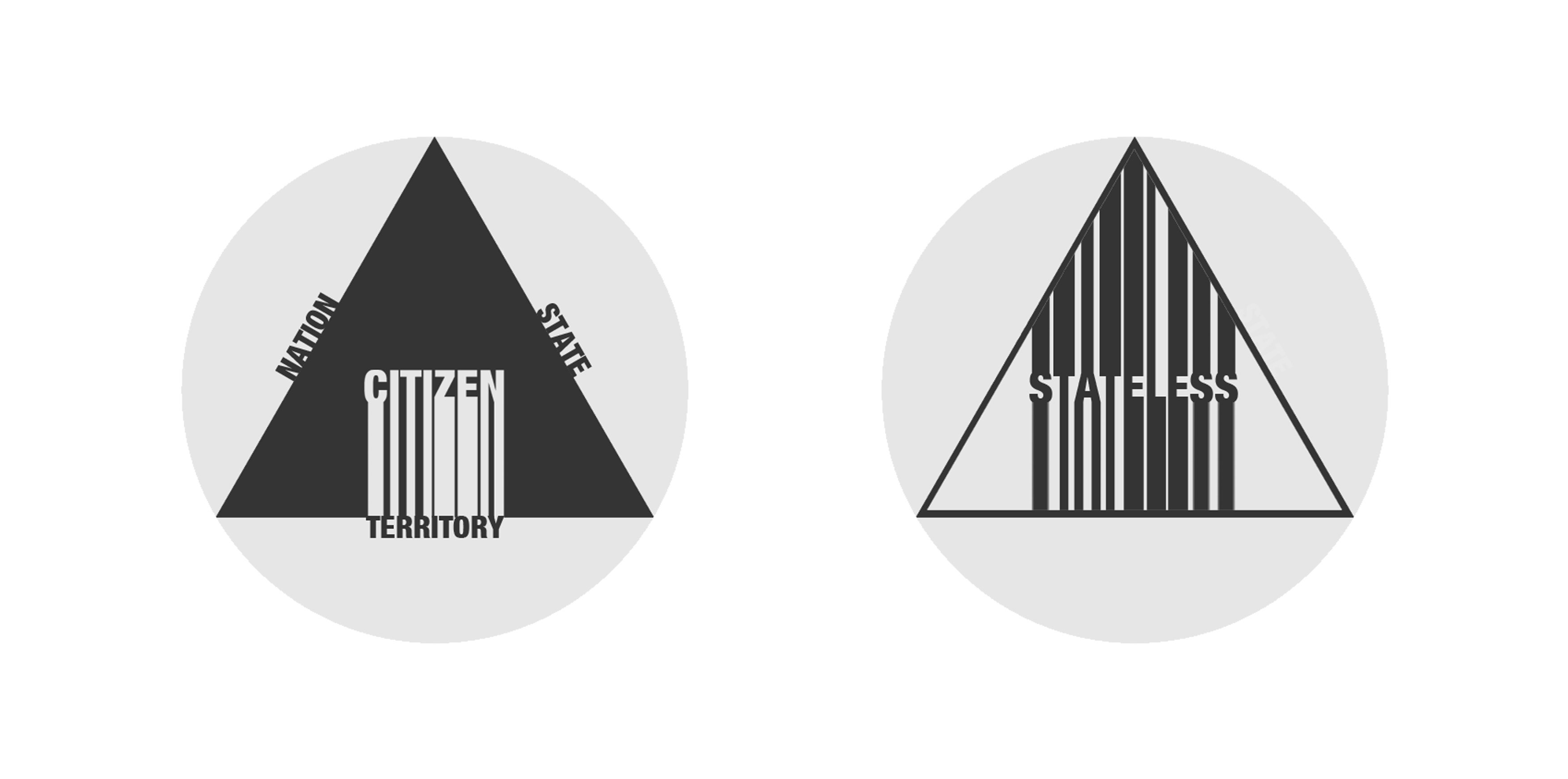

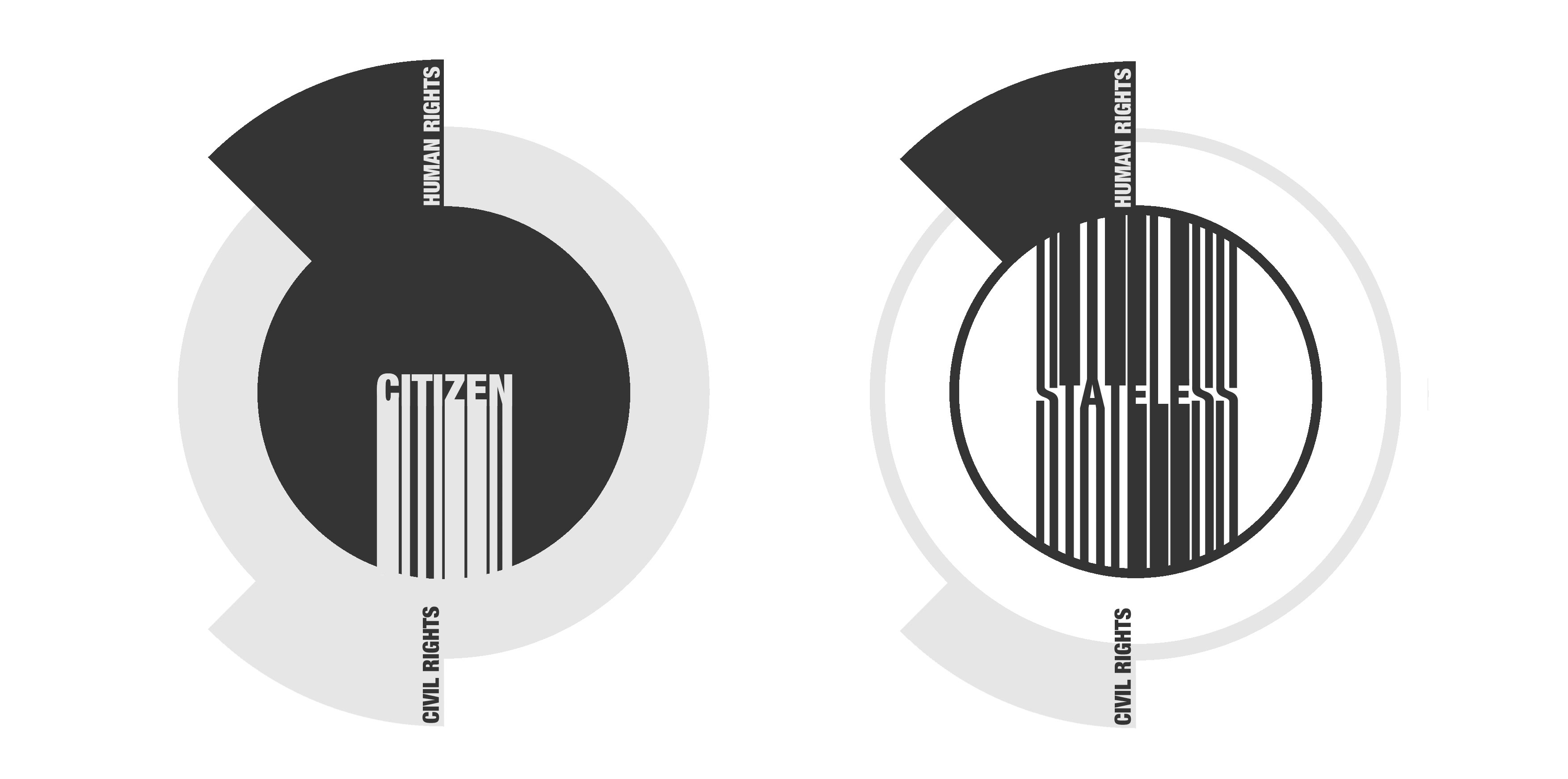

A citizen is a member of and integral to any governmental system. His/her rights, human and civic, are protected by the hierarchy that exists in the state/nation/territory triangle. The state of displacement radically questions this hierarchy, creating tension between ‘man’ and ‘citizen’, human and civil rights, and nativity and nationality.

What is the difference between the citizen and the displaced?

A ‘displaced’ person is one who lives outside his/her country of nationality for reasons of immigration, refuge etc., or who is not considered a nationally of any state, under the operation of its law (Arendt).

Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben argues that in a world of constant motion and circulation, man, as a politi- cal being, can no longer thrive ‘only as a citizen’ unless changes are made to the way we perceive a person in relation to the state, the nation, and the territory. Man’s political survival is imaginable only with the introduction of ‘extraterritories’ or ‘aterritories’ in strategic locations – especially in areas of high diversity or tension. ‘A space that does not coincide with any homogenous national territory, nor with their topographical sum, but would act on these territories’, an extraterritory ‘[makes] holes in [these territories] and [divides] them in a Mobius strip where exterior and interior are indeterminate’. An extraterritory is a space that does not completely abide by the jurisdiction of any state under the operation of its law.

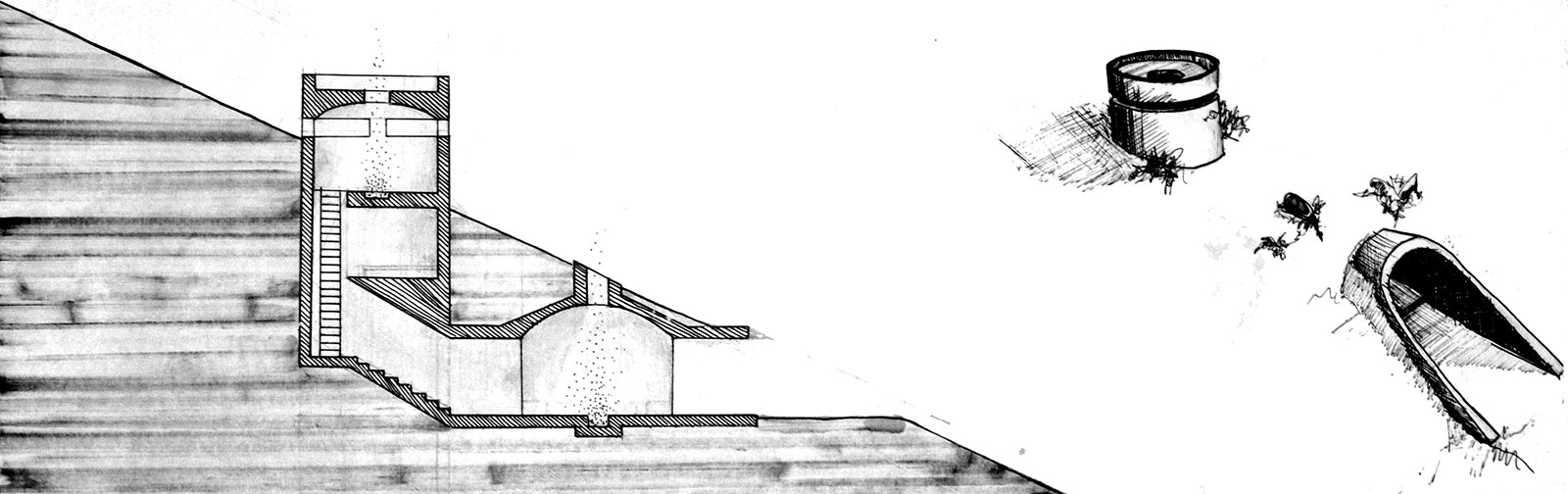

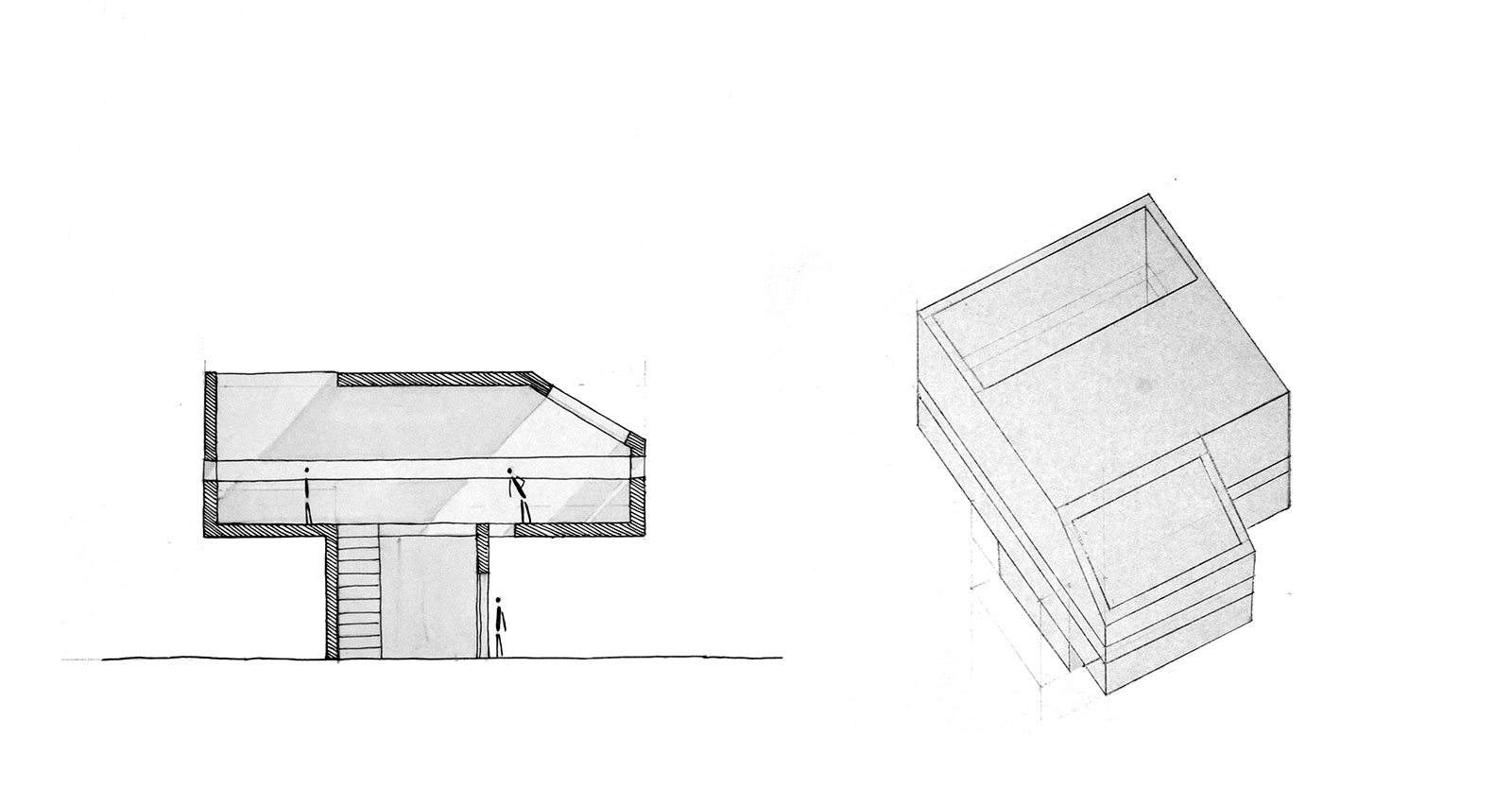

Here, we analyze the relationship between the displaced and the extraterritory, exploring it’s spatial/ architectural manifestation and impact in Lebanon, ultimately applying my understanding of relationships be- tween individuals that cannot be described simply as ‘citizens’ and the land they live to an architectural setting. I aim to offer an alternative to the established system and modes of spatial production, not a utopist solution, potentially culminating in the design of a communal living space; a sustainable co-housing project, the user groups of which consist of stateless individuals, refugees, and people who can afford and want to question their relation to the state in which they live. The space will serve as an interface – an extraterritory – for users to come together and benefit from one another; physical proof of the possibility of alternative ways to socially, politically, anthropologically, and spatially function and develop.

1

THE CITIZEN VS. THE DISPLACEDTo understand the status of a refugee or of a displaced person, it is crucial to understand the status of the displaced person’s core opposite, the citizen, one who is grounded and stable.

A citizen by definition is the legally recognized subject or national of a state, either native or naturalized. He/ she is a member and a core element of a governmental system.

According to the Declaration of Human Rights, a citizen is a member of a nation-state, one delimited by a certain physical territory.

The citizen’s rights (human and civic) are protected by the hierarchy that exists in the ‘state, nation, territory’ triangle:

- the nation, in accordance with its etymon, natio originally meant simply “birth” which implies that birth directly results in a nationality, belonging to a nation

- the state represents sovereignty of the governmental system

- the territory delimits the physical land that is subject to that sovereignty.

A displaced person or a refugee is one who radically calls into question the ‘state, nation, territory’ hierarchy. Once a person loses his/her citizenship i.e. once a person is not recognized as a citizen by any nation-state, his/her civil rights and his/her human rights, by consequence, are no longer recognized nor ensured. The displaced person (or the refugee) creates tension between ‘man’ and ‘citizen’, human rights and civil rights, nativity and nationality.

“The concept of the Rights of man,” Arendt writes, “based on the supposed existence of a human being as such, collapsed in ruins as soon as those who professed it found themselves for the first time before men who had truly lost every other specific quality and connection except for the mere fact of being humans.”

In the nation-state system, the so-called sacred and inalienable rights of man prove to be completely unpro- tected at the very moment it is no longer possible to characterize them as rights of the citizens of a state.

— Giorgio Agamben on Hannah Arendt’s We Refugees

Citizen the core of the ‘Nation, State, Territory’ triangle, which in return protects the Citizen’s civic andhuman rights.

Citizen the core of the ‘Nation, State, Territory’ triangle, which in return protects the Citizen’s civic andhuman rights.Stateless calls into the question the ‘Nation, State, Territory’.

Citizen his/her human rights are ensured and pro- tected by his/her civil rights

Stateless his/her human rights fade away with his/ her civil rights. Stripped of political identity, the State- less becomes a barcode, a mere number in sta- tistics. The Stateless creates tension between the concepts of Man vs. Citizen.

HOMO SACER

Homo Sacer, according to Agamben, is an individual who is reduced to ‘bare life’, i.e. stripped from any political definition. Homos Sacer is a person who is deprived of all rights and all functions in civil religion because of being outside or beyond the law.

In Roman law, Homo Sacer represented a person who is banned from the system, who may be killed by anybody with impunity and may not be sacrificed for religious purposes.

In the Hebrew language, Homo Sacer is one who is ‘set apart’ from common society, one who is cursed.

TYPES OF DISPLACED INDIVIDUALS

DE JURE a person who isn’t considered as a national by any state under the operation of its law.

DE FACTO a person who is outside the country of his/her nationality for several reasons (economic, political, social, etc...). Examples would be a refugee or an immigrant.

2

EXTRATERRITORIES

In a world of constant motion and circulation, Giorgio Agamben argues that man, as a political being, can no longer thrive ‘only as a citizen’ unless changes are made in how we perceive a person in relation to the state, the nation and the territory. According to him, man’s political survival is imaginable only if we introduce what he calls ‘extraterritories’ or ‘aterritories’ in strategical locations, especially in areas of high diversity or tension. An extraterritory, according to Agamben, is ‘a space that does not coincide with any homogenous national territory, nor with their topographical sum, but would act on these territories, making holes in them and dividing them in a Mobius strip where exterior and interior are indeterminate’. An extraterritory is a space that does not completely abide to the jurisdiction of any state under the operation of its law.

![]()

As is well known, one of the options considered for the problem of Jerusalem is that it becomes the capital, contemporaneously and without territorial divisions, of two different states. The paradoxical condition of reciprocal extraterritoriality (or, better, aterritoriality) that this would imply could be generalized as a model of new international relations. Instead of two national states separated by uncertain and threatening boundaries, one could imagine two political communities dwelling in the same region and in exodus one into the other, divided from each other by a series of reciprocal extraterritorialities, in which the guiding concept would no longer be the ius of the citizen, but rather the refugium of the individual.

Today, in a sort of no-man’s-land between Lebanon and Israel, there are four hundred and twenty-five Palestinians who were expelled by the state of Israel. According to Hannah Arendt’s suggestion, these men constitute “the avant-garde of their people.” But this does not necessarily or only mean that they might form the original nucleus of a future national state, which would probably resolve the Palestinian problem just as inadequately as Israel has resolved the Jewish question. Rather, the no-man’s-land where they have found refuge has retroacted on the territory of the state of Israel, making holes in it and altering it in such a way that the image of that snow-covered hill has become more an internal part of that territory than any other region of Heretz Israel. It is only in a land where the spaces of states will have been perforated and topologically deformed, and the citizen will have learned to acknowledge the refugee that he himself is, that man’s political survival today is imaginable.

— Giorgio Agamben on Hannah Arendt’s We Refugees

Today, in a sort of no-man’s-land between Lebanon and Israel, there are four hundred and twenty-five Palestinians who were expelled by the state of Israel. According to Hannah Arendt’s suggestion, these men constitute “the avant-garde of their people.” But this does not necessarily or only mean that they might form the original nucleus of a future national state, which would probably resolve the Palestinian problem just as inadequately as Israel has resolved the Jewish question. Rather, the no-man’s-land where they have found refuge has retroacted on the territory of the state of Israel, making holes in it and altering it in such a way that the image of that snow-covered hill has become more an internal part of that territory than any other region of Heretz Israel. It is only in a land where the spaces of states will have been perforated and topologically deformed, and the citizen will have learned to acknowledge the refugee that he himself is, that man’s political survival today is imaginable.

— Giorgio Agamben on Hannah Arendt’s We Refugees

3

THE REFUGEE“Owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of their nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail themselves of the protection of that country or return there because there is a fear of persecution...”

That there is no autonomous space within the political order of the nation-state for something like the pure man in himself is evident at least in the fact that, even in the best of cases, the statues of the refugee is always considered a temporary condition that should lead either to naturalization or to repatriation. A permanent status of man in himself is inconceivable for the law of the nation-state.

— Giorgio Agamben on Hannah Arendt’s We Refugees

REFUGEES AND THEIR FATES IN LEBANON

1

NATURALIZATION | ARMENIANSNaturalization

to be admitted to the citizenship of a country

to move from the state of a ‘refugee’ to the state of a ‘citizen’

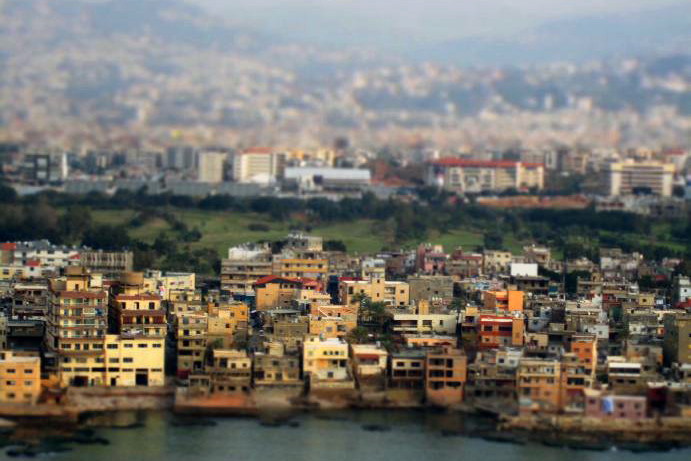

Bourj Hammoud and Qarantina

In 1919, about 200 000 Armenian Refugees arrived to Lebanon from the area of Cilicy. The refugees settled in camps set up in Qarantina and Hajen, in shelters made out of tin, wood and hay.

In 1929, when the Lebanese Government decided that the Qarantina area was to be evacuated, the Armenian refugees gradually moved into Bourj Hammoud, where construction og houses, schools and Churches began, organized mainly by local humanitarian organizations.

In 1948, about 10 000 Armenian refugees fled Palestinian lands and came to settle in Bourj Hammoud. In 1953, Armenians gained representation in the Lebanese government.

Aanjar

In 1919, the seven Armenian villages of Moussa Dagh in the Gulf of Alexandretta resisted to Turkish invasion and were eventually rescued when the French expanded their Syrian dominions north. In 1939, Paris exchanged that region with the promise of Turkey’s neutrality in the conflicts, transforming Moussa Dagh to Turkish land. The French evacuated 5500 Armenians living there to a plot in the Bekaa. Conditions were harsh at the beginning but in time the town of Aanjar developed.

2

NATURALIZATION | SYRIANSRepatriation

to go or to be sent back to one’s original country

to move from the state of a ‘refugee’ back to the state of a ‘citizen’

The number of refugees has nearly doubled in three months. In September 2012, UNHCR counted 58 000 registered and 23 000 unregistered refugees in Lebanon. Today, UNHCR counts 120 000 registered refugees and 26 000 unregistered ones.

Today, Syrian Refugees are scattered all around the country. Some can afford to rent apartments, some share apartments with other families but the majority aren’t that fortunate. Most refugees today live in tents, in schools, in Mosques or squat abandoned buildings,...

Sabra & Shatila

A number of Syrian refugees have moved into shared rented apartments in Sabra & Chatila.

A lot of these refugees have chosen not to register with the UN:

‘We rather live privately in squalor than publicly in a tent full of other refugees’.

When asked about why Sabra & Chatila was chosen, refugees explain how Palestinians can relate to the suffering they’re going through.

Families sharing the same apartment live by concepts of sharing. They rely on a small group of Syrian active members who collect money, buy and distribute food: ‘If I just have one Lira, it means that everyone has one lira, and we can manage ourselves’.

Bekaa

In the Bekaa, families live in tents, Mosque complexes or schools. Some are hosted by Lebanese families, some squat, and a small number rent apartments. The Lebanese and international organizations such as the UNHCR and the DRC have been helping the refugees since the conflicts began, but as time passes, ressources have thinned.

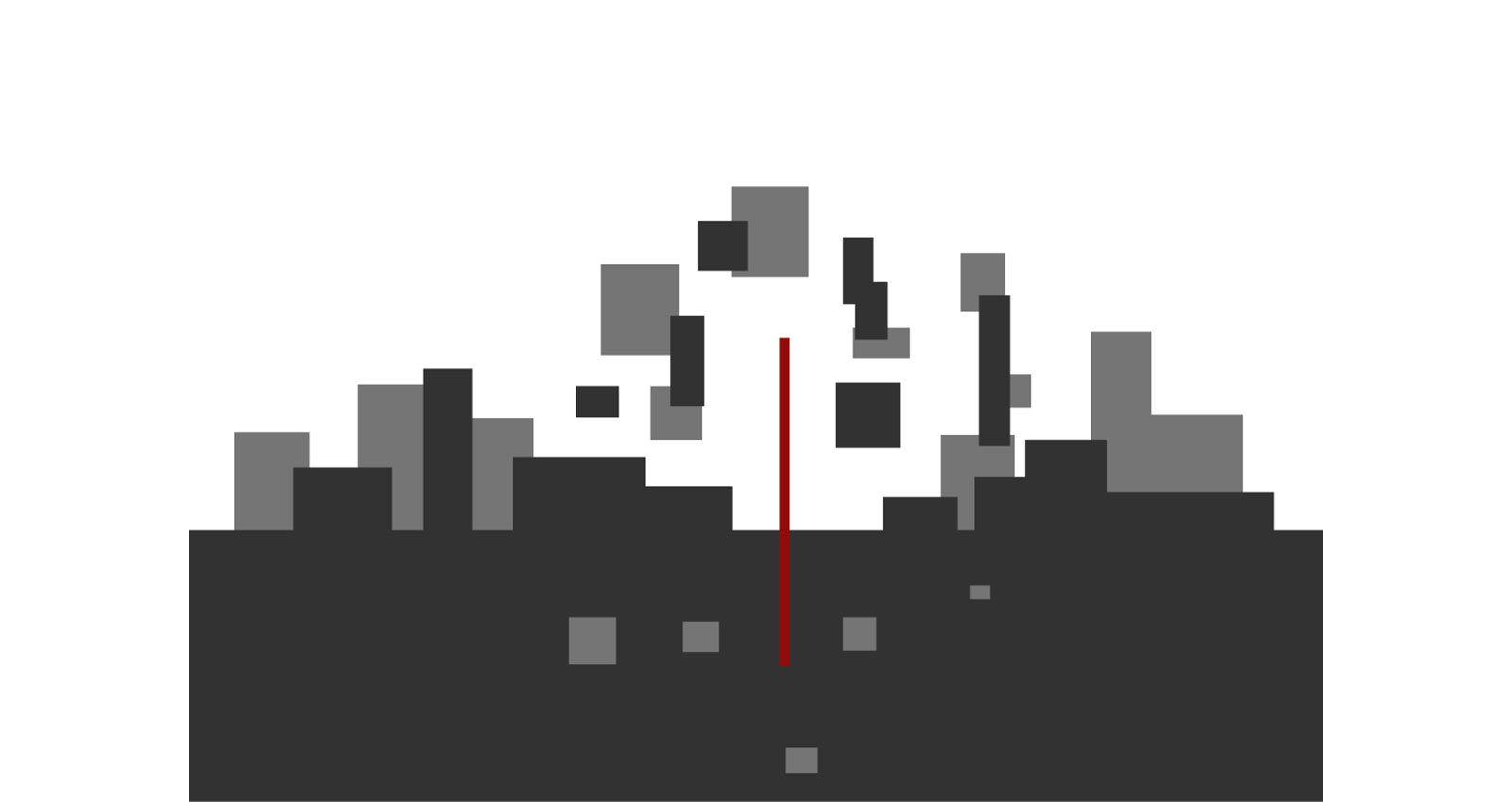

Diagrammatic representation of state of Syrian refugees

in the Bekaa Valley & Sabra and Chatila

Defying displacement by creating a space of anchorage

in the Bekaa Valley & Sabra and Chatila

Defying displacement by creating a space of anchorage

Diagrammatic representation of state of Syrian refugees in Sabra and Chatila

Overpopulated hiding spaces

Overpopulated hiding spaces

Syrian Refugees in Lebanon between October and December 2012

3

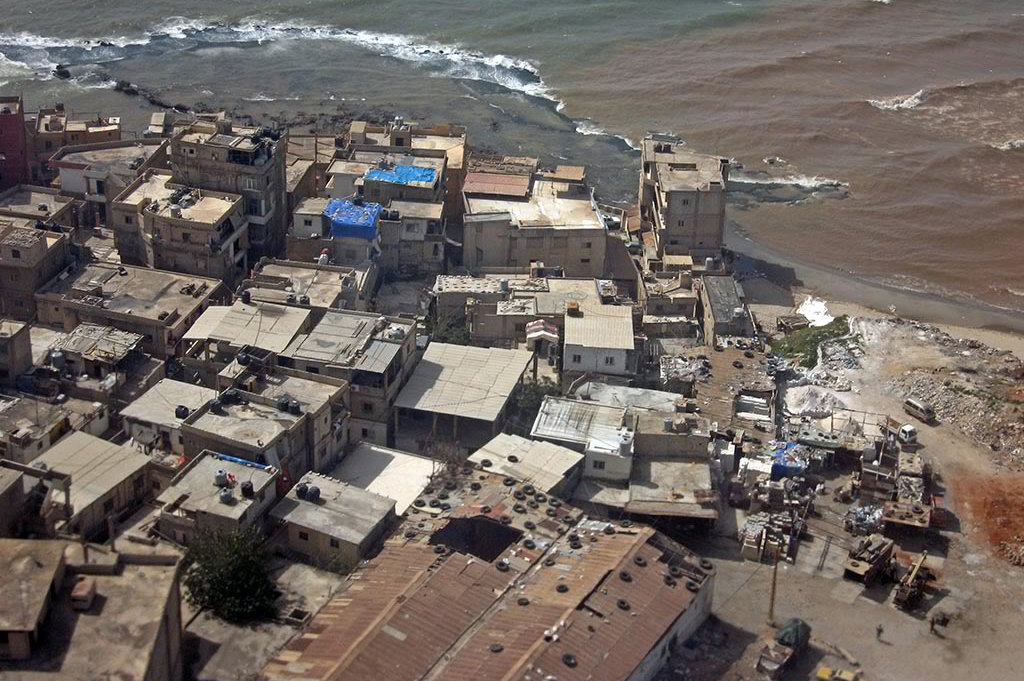

STATE OF LIMBO | PALESTINIANSEven after more than 60 years, most Palestinans have not been naturalized nor repatrated, but remain in a state of political paralysis.

In 1948, 85% of the Palestinians left their homes either by force or because of fear, fleeing the West Bank and the Gaza to Lebanon, Syria and Jordan.

In Lebanon, 16 camps were set up all over the country, with over 400 000 refugees living in them.

12 of these camps still exist today, 4 are destroyed.

Owing to their political status, the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon are deprived of certain basic rights such as owning land or working in a number of professions.

4

EXTRATERRITORIES IN LEBANON

1

AARSAL

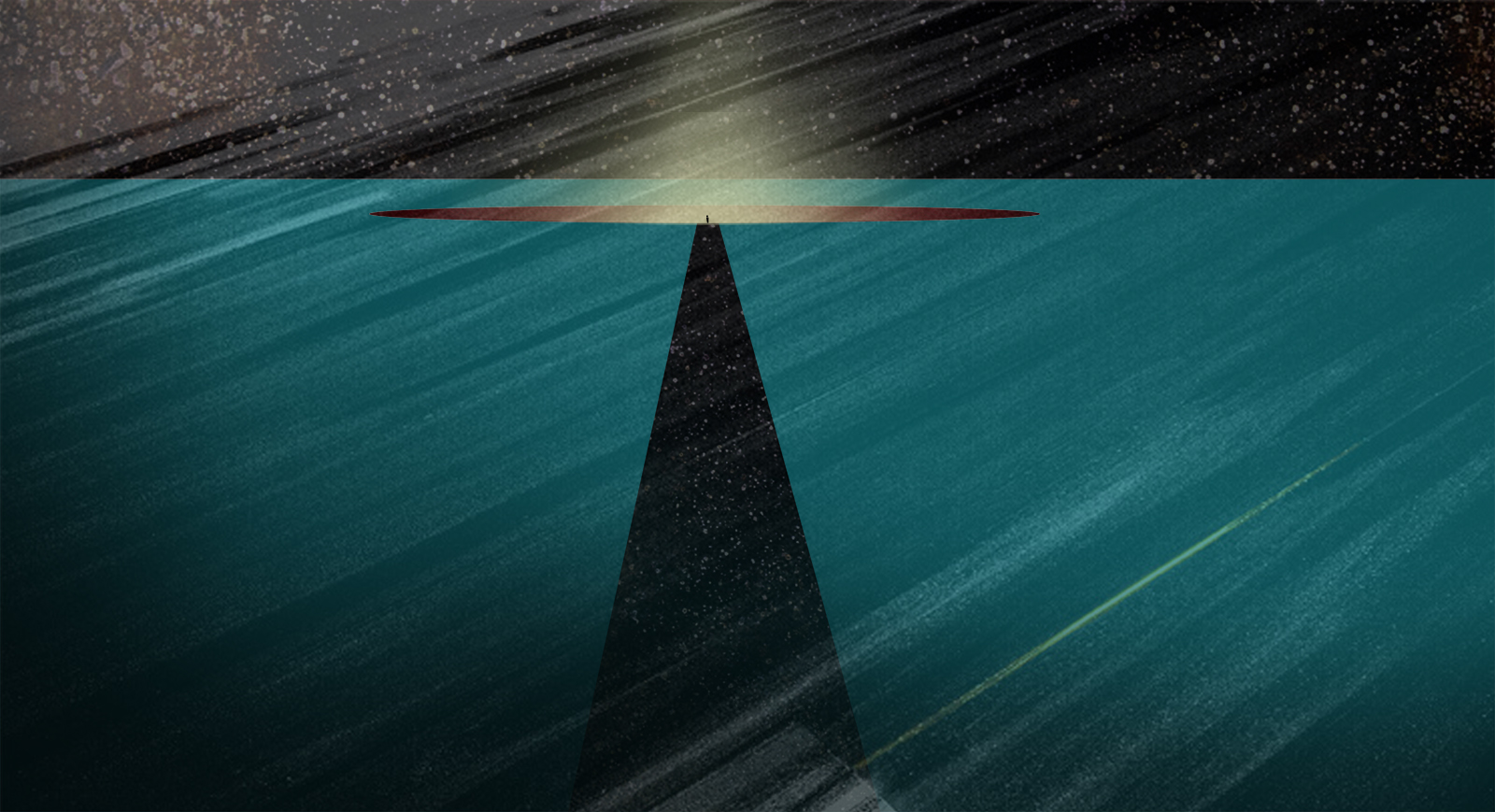

IGNORES TERRITORIAL LIMITS AND HOUSES THE NEO-CITIZEN- Questioning territorial limits – ambiguity of territory and boundary Citizens that do not recognize territory

- Identity and belonging are questioned

Aarsal is a region located in the north of the Bekaa valley on the Syrian border. Distanced 122 km from Beirut and 12km from the Syrian border, the town of Aarsal offers great insight to the functioning and spatial produc- tion of an extraterritory not only because it house a sizeable population of ‘displaced’ individuals (Syrian refugees), but also because it is home to ‘citizens’ of an extraterritory, Aarsal.

To many visitors, Aarsal, located on the border between two countries is seemingly more a part of Syria than it is of Lebanon, due to facts such as the selling of a big number of syrian products in the area.

With many of the town’s main arteries leading to Syria past unmonitored borders, Aarsal demonstrates how the network of relationships and interactions can be a-territorial, i.e. ignore the territorial, national limits. Commerce and trade do not recognize boundaries in this region and It is said that the inhabitants of Aarsal have kept the relationships and flows of interaction that existed in the region prior to the establishment of the counries of Lebanon and Syria, relationships dating back to the Ottoman Empire.

The fact that it is said that there are parts of the town inaccessible to the Lebanese Army or that the Syrian Army has freely searched houses in Aarsal are factors that question Aarsal’s belonging to Lebanon.

With the eruption of the clashes in Syria, a very big number of Syrian refugees have crossed the border and settled themselves in bordering Lebanese towns such as Aarsal.

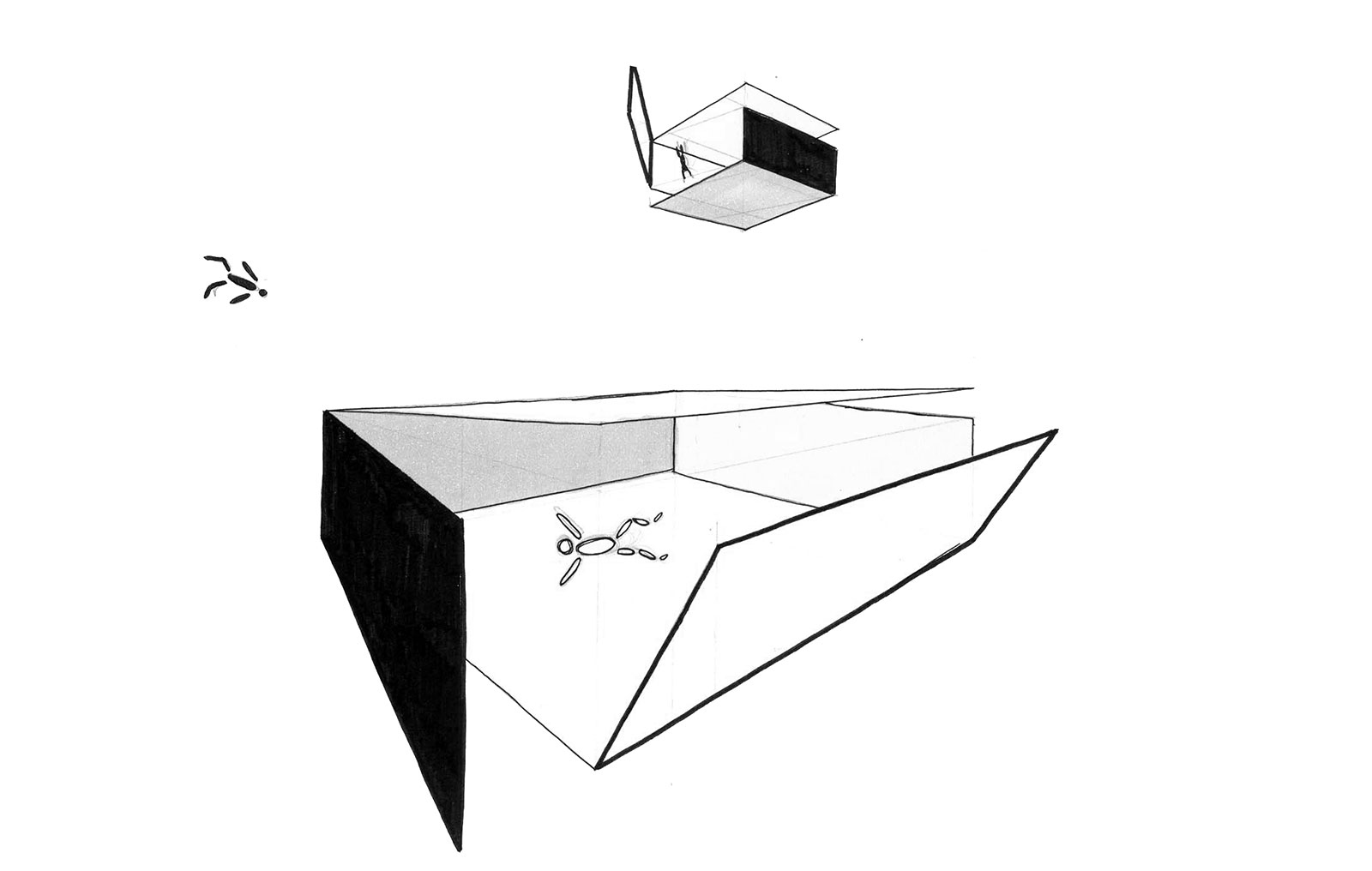

Aarsal ignoring territorial limits, defying the conventional type of interactions

existing between the two countries and creating extraterritorial bonds

existing between the two countries and creating extraterritorial bonds

The permanent residents of Aarsal -citizens of the extraterritory- are grounded

and in a position of observation.

The refugee in Aarsal -the displaced- tries to ground himself/herlsef

as much as possible to defy this displacement.

The displaced tries to keep to himself/herself.

![]()

as much as possible to defy this displacement.

The displaced tries to keep to himself/herself.

A refugee is a living, foundational challenge to the truisms and reifications of the nation-state system, as an interruption to or aberration of ‘the proper and enduring form of political identity and community- that is the citizen and the sovereign nation-state’.

— Hannah Arendt in Views on the camp: Theories and Methods in Unsettling Refugees

2

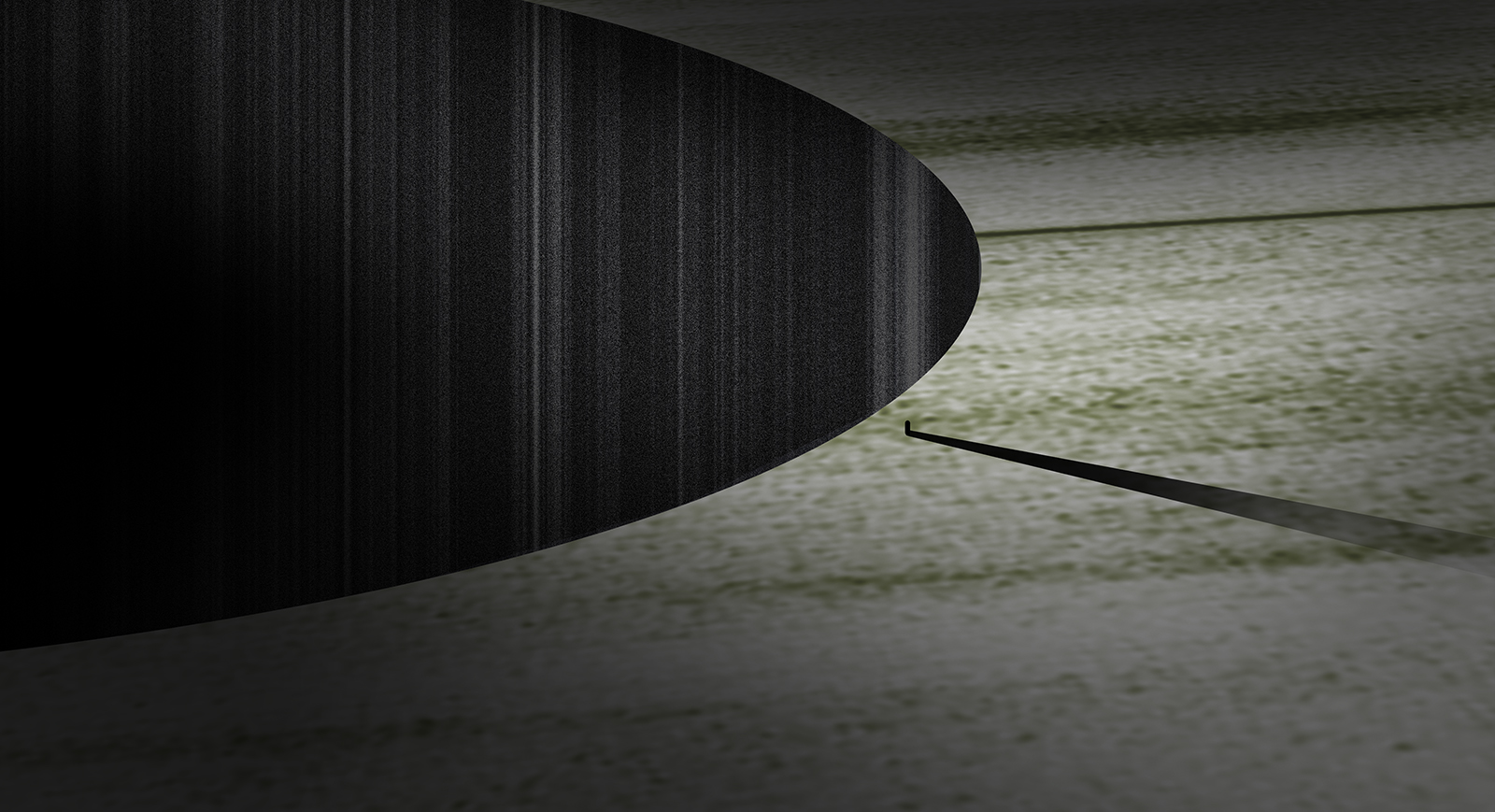

SABRA & SHATILA

SQUATTING AS A CLAIM TO NATIONAL IDENTITY AND BELONGING TO A SPACE THAT LIES OUTSIDE THE DOMAIN OF THE HOST SPACE - Mental image of extraterritoriality

- Not an economical/ urban extraterritoriality

- Ambiguity in social/ political identity and belonging

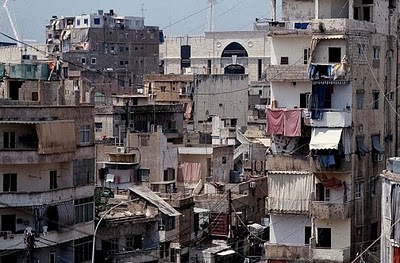

Today, Shatila appears to blend with the urban fabric that surrounds it, but a walk through it makes most feel like they’ve entered somewhere different. Tall buildings compossed from gradually stacked floors take the pedestrian through narrow lanes with hanging electricity cables.

Shatila was established by the UNRWA, The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, in 1949 for the Palestinian refugees that have been landscaped out of their homes in the West Bank and Gaza.

The UNRWA defines a Palestinian refugee as “any person whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948 and who lost their home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict” (Shafie).

For many years, the Lebanese Government hindered the development of the camp from temporary shelter to a permanent one for reasons such as some claiming that the presence of Palestinians fluctuates and threatens the fragile Lebanese sectarian balence.

During the civil wae, Shatila underwent horrible events such as the 1982 massacre by Christian Phalangist militias and the 1985-87 conflicts between the Shiite Amal and the Palestinian refugees, making the area an iconographic center of Palestinian suffering in Beirut.

With their presence in Lebanon associated with the Civil War, the Palestinian refugees constituted an entity whose presence was perceived as a threat to Lebanon’s political stability and its delicate sectarian balance.

Shatila has become an enclave detached from the city of Beirut and non-existent in the perception of many Beirut residents.

Sabra & Shatila squatting as a claim to a national identity and belonging to a space

that lies outside of the host space

that lies outside of the host space

3

JNAH

A SPACE THAT BREAKS SOCIAL BOUNDARIES -

Marginalized by the city

-

Ignores existing socio-political relations and prejudices

Marginalized by the new highway connecting the airport to Municiplal Beirut, with rent and squatting as the normative form of inhabitance and settlement there, Jnah exhibits strong conditions of contested land ownership.

Jnah’s infrastructure and buildings tell clearly of the mild forms of self-regulation and organization the area enjoys. With no thorough authoritative governing, buildings and informal housing structures violate building regulations, and the quality of construction is poor, even sub-par.

Initially populated by rural migrants and people displaced bevause of the Lebanese civil war, Jnah today enjoys a more diverse population comprising a number of immigrant workers who now live there as well.

While in other parts of the Beirut, ethnic minorities are notably marginalized, voiceless, and often discriminated against, the spatial, organizational, and authoritative configuration of Jnah has allowed the development of different relationships with such groups. The marginalized urban strip hosts equal-opportunity interactions between its inhabitants, fueling a more socially encouraging environment nurtured by ethnically, economically, and socially diverse users.